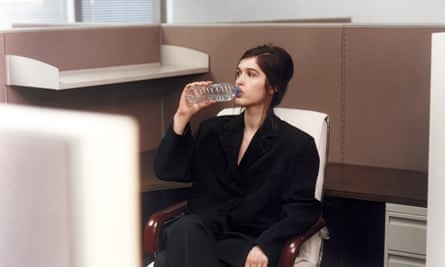

In Marie Davidson’s nightmares, she’s always darting between spaces. The French-Canadian performer spent the better part of last year touring and the staircases, parking lots, corridors and succession of people filtering through her subconscious are telling. “I find myself in a place, not wanting to be there, knowing that I have to be in another,” she says of her dreams. She is a rueful, self-described workaholic, travelling from one club, transport interchange or professional milestone to another. Pursuit, in its various forms, runs through Davidson’s life.

Long before her transformation into a self-trained electronic musician, known for droll spoken vocals and tough hardware, she was playing guitar, violin, and keyboards in Montreal’s experimental DIY scene. She frequented parties as a wide-eyed teenager with an affinity for 90s hip-hop and R&B. By her 20s, her relationship with club culture – now with a taste for techno and Italo disco – matured into the dynamic she critiqued on her 2016 album Adieux au Dancefloor and continues to rebuff on her new album Working Class Woman, where industrial batterie and bleak introspection is lightened by wit and a forthright kick drum.

The inspiration she first felt in clubs waned into anxiety. What began as “pure magic”, witnessing a DJ conduct a communion of revelry, gradually became pure malaise. “There’s this endless chase of – it depends, it could be pleasure, distraction, social … I guess it’s a chase against loneliness. I totally include myself in this,” she says. “People want to have a good time, no matter what. No matter how many contortions they have to do, how long of a line they have to wait in outside, how many types of drugs they have to take, they absolutely want to have a good time.” Davidson speaks of her dancefloor experiences like a recurring dream: “It was like the same night over and over again, except for these brief moments when the music was incredible.”

Davidson’s addictive tendencies transferred to a more socially encouraged practice: career obsession and a cycle of self-destruction. “I’m a total control freak,” she confesses. “I am a total maniac who is very hard on myself.” The dark humour behind the robotic caricature of herself on her new track Work It – one that sneers, “Is sweat dripping down your balls?” and laughs, “Well then you’re not a winner yet!” over steely four-on-the-floor jolts – is a vital coping mechanism.

The contemporary standard of success, made even tougher for late-night performers such as Davidson, requires indefatigable production and sustained excellence, no matter what the cost is. “I have this tendency to push myself until … I’ve never reached a limit, but I’m always on the edge,” Davidson says, “I’ve lived my life on the edge for the last few years, and I feel like I can’t do that any more. I just can’t. My body just is not following.”

In the summer of 2016, Davidson had reached what she describes as her “bullshit threshold”. These experiences later became material for a live A/V show of the same name at Phenomena festival that year. At that time, she had moved to Berlin to escape a brief separation with her husband – with whom she also plays in the duo Essaie Pas – and was rushed to hospital for emergency surgery. These moments of personal crises prompted her to turn inwards and retreat into a space of self-reflection that she calls “the tunnel”. Unlike the shadowy symbolism of Davidson’s nightmares, the tunnel is a crawlspace of her own invention, where she confronts the shards of her psyche. “A place in my imagination that embodies and represents a state of mind where I am when I get really dark, and I get helpless,” she says. “When I lose all sense of hope.”

This strife taught her an important lesson: she could no longer expend her energy on “trying to be right with everyone”. Shirking the unrealistic expectations of her life and career as a woman in her 30s has opened her eyes. “You’re supposed to love work, have tons of friends, you’re supposed to go out, you’re supposed to have kids ... You’re supposed to do everything, but that’s not real,” she claims. “That’s bullshit for me – that’s a persona that consumerism created to sell products.”

Tinkering with sequencers and writing lyrics in the studio is her idea of true enlightenment: the creative side of work is the only time she truly lets herself go. But even though her personal relationship with nightlife has transformed, she still makes music tailored for clubbing. “Those people are my people,” she insists. “I will never deny my people just because I decide to change.”

Davidson now works with a psychoanalyst using Jungian techniques to make sense of her nightmares. What she’s grown to understand is that the source of her subconscious tension is not necessarily bad or dark, but rather the unacknowledged parts of herself manifesting in menacing, stressful forms. She’s learned to reconnect with these hidden facets and to discard the rest. Davidson reminds us that self-knowledge is a harrowing, ever-evolving process – one that requires humour as much as industriousness.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion