If anyone was destined to make our current situation more bearable, it’s Thundercat. Not only has the bass-playing, kitten ear-wearing, genre-blurring musician just released a new album – let’s call it a self-isolation soundtrack. But, having worked with the likes of Snoop Dogg, Childish Gambino, Pharrell Williams and Erykah Badu, he has enough entertaining stories to last a lockdown.

Such as the time he met Prince at one of the late star’s infamous house parties. “I was drunk, dancing, and he walks up and he’s got them platform sandals, and he’s got his shirt all shiny and stuff. And he goes: ‘That’s not how you do the James Brown [shuffle].’ And then he promptly did the James Brown in sandals, but I think he had just had hip surgery. So I think he may have moved a little too quick.” Or when Joni Mitchell mocked him when she saw his leg tattoo of his bass hero, Jaco Pastorius. “They were close friends and played together. She said to me: ‘Man, I loved him too, but I wouldn’t get him inked on me.’ And everybody laughed.”

We meet in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in mid-March, when things have already started seeming strange. “It feels like the opening scene in The Big Lebowski, tumbleweed blowing down the street,” says the 35-year-old, real name Stephen Bruner. Just like any other pre-show interview, we are sitting in a hotel restaurant. Except this time there is no show. A theatre looms opposite, its neon sign unlit, the words “postponed” glaring out front. Everything is closed. A week previously, Brad Pitt had been spotted at Bruner’s LA gig – “it was pretty wild,” he concurs. But now: tumbleweed. As with so many musicians this spring, the rest of his tour has been cancelled.

And yet, Bruner seems unfazed by the global pandemic taking place outside, or the fact he is about to release a fourth album in the middle of it. “I think I’ve just accepted that everything is terrible,” he says. This lockdown is “what has to happen because our president’s a jackass. He let the coronavirus in. He just let it in. And probably had the intention to let it in just enough so he could get to [save the day and] stay president. Backfire!”

That attitude might sound a little nonchalant, but this has become a bit of a running theme. His new album is titled It Is What It Is, as if serving as a shrug of acquiescence at how unexpected and vicious life can be, after a few unusual years. In 2017, his screwball, falsetto-funk album Drunk, a 26-track joyride through subjects as disparate as police brutality and being friend-zoned, had taken him to a much wider audience. It featured stars such as Pharrell, Kendrick Lamar and Mac Miller, appeared in best album lists everywhere and made genre hilariously irrelevant as he took out big, fat, fluorescent marker pens and liberally daubed over jazz-funk fusion, cosmic soul, prog, R&B and lurid comedy skits like a 21st-century Frank Zappa.

Until then, Bruner had been best known for being the oddball bass player who contributed to Lamar’s seminal To Pimp a Butterfly – winning a Grammy for the track These Walls – as well as nimble noodling on childhood pal Kamasi Washington’s acclaimed jazz album The Epic, various releases by Flying Lotus (his longtime co-producer), including their soundtrack for Donald Glover’s hit TV show Atlanta, and on Mac Miller’s 2018 album Swimming. After Drunk’s success, Bruner puts it casually, he felt “like I woke up in a different place”. He is now an eccentric visionary as likely to appear on the cover of experimental music magazine The Wire as he is to perform on primetime American chat show Jimmy Kimmel or have his songs covered by Ariana Grande.

Yet despite this upward trajectory, the lows have been tough to take. Bruner struck up a close friendship with Mac Miller – you can see their doe-eyed bromance in their Tiny Desk concert video in August 2018. But it was the last performance Miller would do: a month later he died, aged 26, from an accidental overdose. Bruner spoke to him the night before; in the morning, he was gone. “It scared the shit out of me,” says Bruner. Did he know Mac was in trouble? “I mean, we were in trouble,” he says, twirling one of his thin, bleached dreadlocks, “but you don’t realise it all the time. It’s sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. It’s real. You ride the line, you don’t know how close you are sometimes. Do I think he meant to die? No, I don’t think he did. Even though that sometimes creeps in there because you’re always on the edge of a knife. Sometimes you mess up. That happens a lot.”

Miller’s death made Bruner confront some hard truths about his own lifestyle. “I’ve been drinking forever,” he says. “It’s such a part of me. I was always that guy who’s missing one of his shoes, covered in blood.” He knew something had to change. “I couldn’t do the same things I’d done before,” he says. “Witnessing my best friend pass away under such dark pretenses … I’ve done that already. I watched it happen to Austin Peralta,” the late musician about which much of 2013’s Apocalypse was written. “I was posed with this moment where it was like: either it’s your turn to go or you walk the other way. That’s what it felt like. You’re gonna stop or you’re gonna die.”

He got depressed, and then he got dumped, just before he was about to propose. “My best friend died and then the person I was in love with left me within the same couple of months,” he says. “In my mind, I was right on the verge of getting married. And it broke my heart.” After that, Bruner brought in some radical self-care measures. He stopped drinking, took up boxing and started being smarter about food. He’s not sure whether he’ll give up alcohol for good yet but adds: “I just go with how I feel, and how I feel is that that part of my life has stopped. I am a different person right now.”

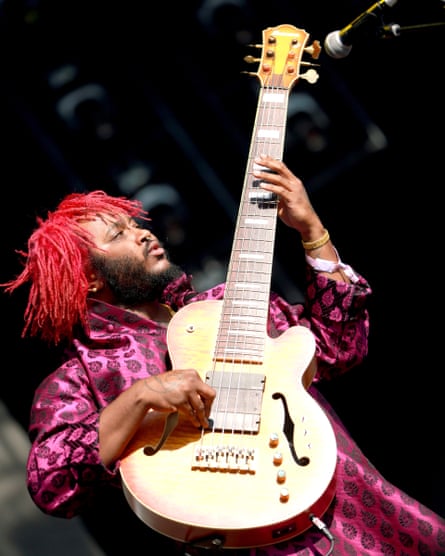

Bruner is a little more designer these days, with Gucci in place of the Native American headdresses and kneepads he used to wear. He is more philosophical in person than his George Clinton-rivalling style suggests, though that doesn’t mean he won’t tweet about “beating the meat”. His new album reflects this duality. Building on the squelchy hot mess of Drunk, It Is What It Is combines bananas interludes with songs about heartbreak, loss and, to quote one song title, “existential dread”. Fair Chance, featuring rappers Ty Dolla $ign and Lil B, is a stunning tribute to Miller, Bruner’s lambent bass sounding like rippling streams underneath. Unrequited Love pulls no punches about loneliness. The lyrics are as scrapbook-specific as they are funny: on Dragonball Durag, he sings to a potential lover: “I may be covered in cat hair but I still smell good.”

Bruner says that these tossed-off thoughts help him to live in the moment and face hard truths, just like the work of his comedian friends, of which he has many. (One, standup Zack Fox, appears as a pilot on his new track Overseas.) Music and comedy, says Bruner, “are the places where you have to be most honest. The reason we love guys like Dave Chappelle and Jim Carrey is because they bare their soul. The better you are at that, the better you are at what you do. It’s the same principle with music, especially with jazz: you’re putting yourself out there.”

Bruner’s own forays into furiously fast frettage with his brother Ronald Jr and friends such as Kamasi Washington helped lay the groundwork for LA’s recent jazz renaissance. But Bruner was unconcerned by the genre’s rigid rules: he also liked Slipknot and spent his high school years playing in thrash-punk band Suicidal Tendencies with his brother; he doesn’t see “separation” between scenes.

Bruner’s music frequently steamrolls over notions of taste. To some, the feathery soft-rock sounds of the 1970s often dubbed “yacht rock” denote all kinds of uncool; yet, on Drunk, he teamed up with Kenny Loggins and Michael McDonald and it made perfect sense. He’s also keen to continue to respect legacy. New single Black Squalls brings together 64-year-old Steve Arrington of 70s funk band Slave and 21-year-old the Internet guitarist Steve Lacy (Childish Gambino hops on the final verse). Bruner says that many young musicians don’t know where the music they’re making came from, so it’s “important to show that connectivity”.

Black Qualls also defines “what it means to be a young black artist right now,” says Bruner, such as feeling paranoid, even guilty, about one’s success, and “wanting to hide your ability, just to be OK”. He started delving into deeper subject matter after working on To Pimp a Butterfly. “It became like: what else do you have to say?” says Bruner. “I would walk into sessions,” where Lamar would be giving “his take on what he just saw and what he experienced emotionally. It was breathtaking. And I’d be like: I don’t know what I’m supposed to do with this. Other than that take it and realise that there is so much more that I have to keep pushing the point on.”

With its refrain of “no more living in fear”, the track feels eerily prescient. Bruner says the message is open to interpretation “depending on where you’re coming from – but because of where I come from, it is damn near literal”. In the lyrics he sings: “Wanna post this on the Gram, but don’t think I should.” (At the start of this year, rapper Pop Smoke was murdered in a robbery at his house after posting on Instagram, while in March 2019, Nipsey Hussle was shot dead in a parking lot.) “It’s an unfortunate reality we live in when it comes to stuff like that,” says Bruner.

The unfortunate reality that we are also living in is that, after this interview concludes, self-isolation is on the cards. But Bruner remains unperturbed: he writes most of his music alone anyway, he says, and enjoys spending time with his cat, Tron. “She still pees on everything. It reminds me to stay feral.”

He’s not worried about what happens next. “I’m about as worried as I’ve been since I was five,” he says. “I used to be infatuated with nuclear war. I remember realising then the power that man has over man in general – what we’re capable of doing to each other terrified me. After that, I just accepted it. We just do arbitrary, stupid shit to each other.”

He references the cartoon meme of a smiling dog sitting in a burning house and telling himself: “This is fine.” “The moments that I thought I was gonna die, I was just like, this is fine. This makes sense. It really freaks my friends out because whenever you can see something happening, I calm down. It’s just what it is.”

It Is What It Is is out now

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion